Making the Transition from Development to Design

Translated by Sola | ORIGINAL switch language

A couple months ago, a person emailed me asking for tips for transitioning to design from a development background. As someone who had loosely gone through the same path (from programming to design to programming then back to design), I wanted to share any advice I could possibly give. After writing the letter, I thought it may be useful to a few other people out there. So if you are a developer looking to get into design, this is written specifically for you. To preface, this article is not why developers can be good designers. This article does a great job of articulating those ideas. So instead of duplicating good work, I spent time on some ways a developer can get into design.

Before I get into the meat of this response, I highly recommend you start your transition in the software design world (e.g., web apps, mobile apps, traditional software, etc.). If that is not the case, I highly recommend you reconsider, at least in the short term. I hold the belief that software design is going to be changing a lot in the next 5 years, and those changes are going to greatly benefit people with development and design skills. I think the future designer is going to look and act a lot more like a design technologist. So don’t look at your current position as a disadvantage, view it as a great starting point towards a complementary vocation.

I tried to put together a list of tips that would have been helpful to know when I first got started. The design technologist role was still taking shape when entered the professional sector and a lot of my own progression was from muddling around in the dark. To be honest, I don’t think I would change that even if I had the opportunity to do so. So, while I believe these tips could be helpful, there is something to be said about just getting yourself lost with the faith that you will find your way out and learn something in the process. If there is one thing to take away from this email, it is to refrain from mentally separating design and development. When you are creating wireframes, you are implying code that needs to be written. When you are coding, you are actualizing user experiences. To mentally separate each process is the first step towards viewing the creation of software as an assembly-line process. We have a lot of horrendous software due to that line of thinking.

Remember, these are tips based on my personal philosophy and things that have shaped my approach. A lot of the thoughts below are opinions that a lot of other designers may disagree with. That’s what makes this topic so interesting.

Tip #1: Don’t stop building things

It will not be long before anyone designing software will require an understanding of how to make software. I have been saying this for nearly half a decade and it is finally starting to play out. Developers interested in design do not realize their development background is their greatest asset. Designers will be desperately working to have the skills you already have.

It is important to keep your development skills honed. If your goal is to shift your emphasis towards design, your day-to-day development tasks may change but they can still be used. The most obvious area where they can be used productively is prototyping. As interaction design becomes increasingly complex, prototypes will become a greater necessity. Your coding background will allow you to make more sophisticated, accurate and (hopefully) insightful prototypes. Ultimately, the real goal is to see no difference between your development and design skills. The skills gained from each focus are connected, interdependent and equally important towards making good software.

Tip #2: Learn design in order of dependency

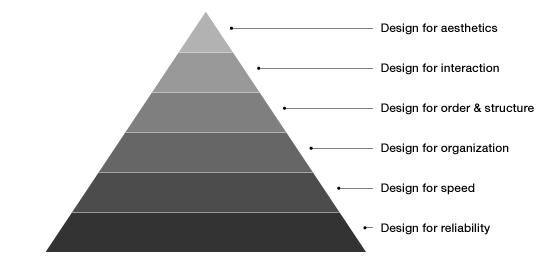

Trying to tackle the entire universe of design at once will set you up for failure. I highly suggest easing into the process. A great way to do this is to start at what is most vital for software (its function) to what makes it delightful to use (its form). A worthwhile read on this subject can be found here. I decided to modify the author’s hierarchy a bit for our case (if you’ve looked at the diagram from the link provided, the list below starts at the bottom and moves up):

These steps gradate from the rational to the emotional. Learning design by progressing through these steps is optimal for two reasons. The first reason is that each tier is dependent on its predecessor—for instance, learning visual design without a strong understanding of interaction design will lead to poor output. The second reason is that this transition gradually moves you from pure logical, quantitative thinking to more qualitative, aesthetic thinking.

The first two steps (design for reliability and design for performance) will probably be areas you’re familiar with. However, it is important to understand how much design can impact the reliability and performance of software. Designing for organization is all about information architecture and content hierarchy. Designing for order and structure relates to traditional interface design (which is traditionally represented with wireframes). Designing for interaction, determines the details of how a human being actually uses software (translating a static interface into a rich interactive experience). Designing for aesthetics is obviously visual/motion design. There are ample material for each of these areas which will be easy enough to find—this article is not about detailing every step, it’s about explaining the progression of learning.

There is another step which does not exist on the pyramid, and it is arguably the most important. The last step is to learn to use all the skills concurrently. The end goal is to not treat these facets of design as separate steps, but as variables in a complex equation that is accounted for throughout the entire process. While the hierarchy of design needs will continue in the order illustrated, the aggregate of all skills are used to solve each need.

Tip #3: Design everything you do

During my first internship out of college, Stella Lai gave me this tip and it has been the best professional advice I ever received. Try to practice this tip as literally as possible. The obvious areas are how you dress and how your house/apartment/room is organized. I would suggest not stopping there. Your emails should be written/composed clearly and beautifully. Your conversations with individuals should be designed through how you listen, how you maintain eye contact, how you respond (both spoken and unspoken). Everything you do should have a reason, no matter how small. Design requires constant practice, this is a great way to keep growing.

Tip #4: Care about your audience

The work you care about will likely turn out better than the work you don’t care about. So what happens in the case when you simply cannot get yourself to care? I advise you to put your focus on the people your work will affect as much if not more than the subject of your work itself. If you care about your audience, you’ll automatically care more about the subject. The opposite is not always the case. The more we put others (the audience) in front of ourselves, the better the results tend to be.

Tip #5: Talk about design and listen even more

Reading is great, but I have learned far more through discussions with experienced, knowledgable and trustworthy people. When you find yourself in such a situation, ask questions and listen. I want to emphasize the importance of truly listening. In the short term, it is important to absorb as much good information as you can while you are in the learning process to challenge your preconceptions and push your thinking. In the long term, it is important because listening will be a vital skill in your practice. The best designers I know are amazing listeners. You will be doing it a lot (with your colleagues, your audience, your clients, etc.), so you should be good at it.

Tip #6: Learn to write, then learn to speak

Early in your practice it will be important to absorb ideas to help you form your own philosophies and approaches. However, at some point (preferably earlier than it is comfortable for you), it will be important to start formulating those points of view to an audience. Thoughts kept in your head have the luxury of being biased, irrational or simply flawed. Communicating those thoughts to an audience and opening them up to scrutiny forces us to improve our thinking. Writing well is also essential to practicing design. I’ve done some of my best learning through writing on my blog. I would suggest blogging as the first step towards sharing your ideas.

In the long term, I suggest trying to speak in front of an audience at least once. Some people love it, others hate it. I have spoken only a half-dozen times or so and I find the process as rewarding as I do terrifying. The skills necessary for successful speaking (e.g., compelling storytelling, brevity, connecting with the audience, etc.) will help you in your daily practice, especially client-facing interactions. Sometimes, communicating the thinking behind your work is as important as the work itself.

Tip #7: Focus on defining and solving problems

A lot of the work you see at design showcase websites are great examples of well executed decorations that lack substance. The people that can perform this type of work are countless and the skills highly commoditized. Avoid pixel-pushing at all costs – your job is to solve problems. View your work through that lens at all times. Always know what problems you are trying to solve while in the process of designing (e.g., people are having a hard time knowing where to go next in a flow, or, the current visual design does not reflect the mood of our brand). Good designers solve problems, great ones ensure they are solving the right ones. Accurately defining the problem goes a long way towards solving it.

Tip #8: Listen to your gut, but trust your brain

Trends come and go, but elegant, rational and utilitarian products never go out of style. It’s not bad to follow your instincts, but always follow up to understand why you did it in the first place. “Because it felt right” is a fine way to start a conversation, but not a good way to end one.

Tip #9: Be your biggest critic

You will never be perfect, but that shouldn’t stop you from trying. There are always areas to grow. Your work and your practice always can (and should) be improved. When in doubt lean towards being too hard on yourself rather than too easy.

Tip #10: learn from the time-tested—and emulate it

Few things prove a design’s success better than how long it remains relevant. Look to the timeless to guide your approach. This need not be limited to software, the thinking behind designing a great chair often parallels the thinking behind designing great software. Understand how others before you have solved similar problems and try to determine why it took the shape it did. Value precedence; it carries considerable weight. Blindly echoing design trends is a great way to have a dated portfolio in a couple years.

Focusing on digital influences to follow, the operating system is one of the most time-tested and finely tuned pieces of software in existence. Explore the nuances, understand the patterns and know them like the back of your hand. When do you use a drop down as opposed to radio boxes? Why? There are smart reasons behind most of these details and they are worthwhile to know.

Tip #11: Ideate romantically, create pragmatically

Our ideas should be bigger than reality, but our execution should be married to it. This allows us to see the grand future of a product while ensuring that it can exist to have any future at all. Both are important, but they can be detrimental if out of balance or practiced at the wrong times.

End:

The design world is in a phase of rapid change. Designers who understand and can work with code are becoming the prototype. Your transition is not going to happen overnight and a lot of your thinking will need to bend. However, I think you will be surprised by how much of your thinking will not. A lot of your shift is about understanding that you have already been creatively solving problems as a developer, and that a lot of that thinking is universal.

P.S: Special thanks to My Best Friend Chēn Chén who give me much help during my translation. :)